Muscular Imbalances – Asymmetries in the Body

Muscular imbalances can occur due to physical inactivity, repetitive strains exerted on the body on a day-to-day basis, or unilateral exercise.

Reading Time

About 8 Min.

Share What Are Muscular Imbalances?

Definition: The term “muscular imbalances” is defined as a lack of balance between functionally opposite muscle groups, such as the abdomen and back or between the left and right side. Muscular imbalance means that the originally balanced state of muscular tension is off-kilter, and some muscles are too tight or some not tight enough, leading to changes in strength and mobility.

If our body is in balance, then the left side is just as strong as the right. However, it’s possible for one of the two sides to become dominant if this balance is brought out of order by different influences, such as only working out on one side.

You can think of the body as a tent that is stretched more on the right side than on the left. It starts out standing tall much like a tent that has been equally pulled tight on all sides, but as it is exposed to rain or wind, it becomes much more vulnerable. Similarly, bodies with imbalances are much more prone to injury than balanced bodies(Dauty et al., 2003; Schlumberger et al., 2006; Yeung et al., 2009; Fousekis et al., 2010; Brockett et al., 2004).

What Are the Causes and Consequences of Muscular Imbalances?

Muscular imbalances are caused by a wide variety of factors: Physical inactivity, undesirable compensating habits developed after injuries, one-sided exertion while playing sports, or continually poor posture. These are just a few examples, all leading to similar aftereffects:

- Irritated joints, tendons, and ligaments caused by not moving properly.

- Greater susceptibility to strains and muscle tears due to mechanical overexertion of shortened muscles and reduced elasticity (Brockett et al., 2004).

- Reduced performance.

One study showed that if there is a muscular imbalance (i.e. change from the normal state) of 15% or more, the risk is 2.6 times higher of these aftereffects or injuries occurring (Knapik et al. 1992).

Recognising Muscular Imbalances

- Firstly, any muscular imbalances can be recognised through physiotherapy assessments, such as a maximum strength test and muscle length test.

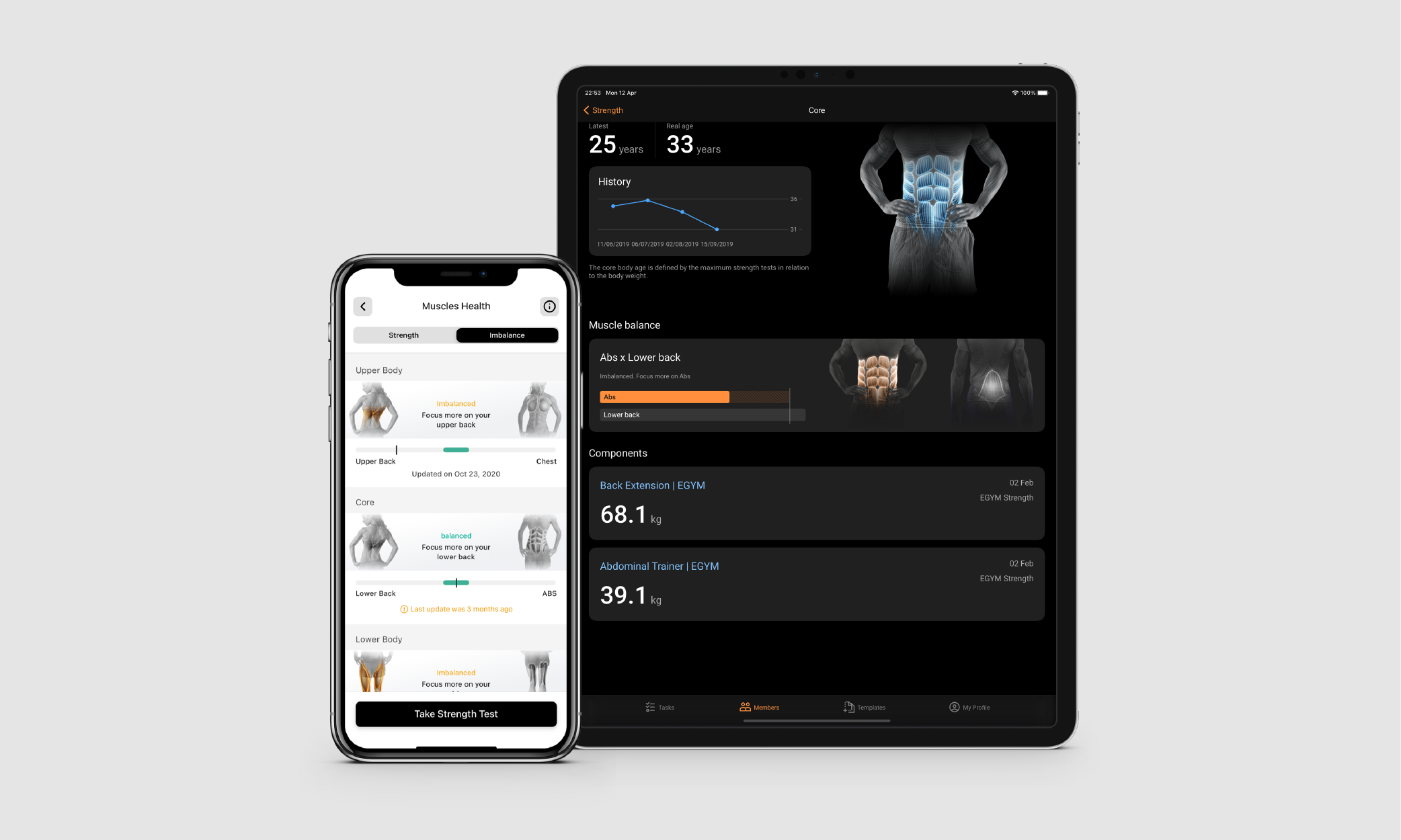

- Working out with EGYM also gives you the chance to find out more about the strength ratios of two opposing muscle groups (e.g. quads and hamstrings). The results of the strength tests on our strength machines are compared and analysed for this. The trainer then uses this data to create a targeted and individual exercise regimen to eliminate any imbalances that may exist. You can find the muscle imbalance analysis in our apps for trainers and members.

Treating and Correcting Muscular Imbalances

Dr. Lutz Vogt, sports medicine specialist at the University of Frankfurt am Main, recommends adjusting workouts if there are muscular imbalances, either to balance them out or to prevent the imbalance from intensifying even further. Shortened muscles should therefore be treated with low-intensity exercises or easy stretching. You can do this before or after exercising or even in separate workouts. In order to correct weakened muscles, you should supplement your usual workout with targeted strength exercises.

Working with EGYM makes it very easy to counteract muscular imbalances. The analysis in the app tells you exactly which muscles to train more intensely in order to correct imbalances. For each important muscle group, there is a specific machine you can use to specifically train and build up the corresponding muscles.

Preventing Muscular Imbalances

There are certain muscles known for their tendency to shorten or weaken as a result of western lifestyles. If it is not possible to individually analyse the muscle balance, muscles that tend to weaken should be trained and muscles that tend to shorten should be stretched as a preventive measure:

Tendency to weaken

- Calves

- Adductors

- Glutes

- Stomach

- Chest

Tendency to shorten

- Anterior thigh

- Posterior thigh

- Lower back

- Hip flexors

Conclusion: Knowledge Helps Prevent or Reduce Problems

If you want to specifically address muscular imbalances, you first need to know how to reliably determine the status quo. EGYM can help make it easy to measure muscular imbalances and clarify them to gym members. The unpleasant consequences of imbalances can thus be prevented and existing problems can be tackled in a targeted manner.

Do You Know the EGYM BioAge?

Find out how gym members can learn more about their own fitness and health with BioAge!

Learn MoreReferences

Fousekis K., Tsepis E. & Vagenas G. (2010). Lower Limb Strength in Professional Soccer Players: Profile, Asymmetry, and Training Age. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 9, 364–373.

Schlumberger A., Laube W., Bruhn S., Herbeck B., Dahlinger M., Fenkart G., Schmidtbleicher D., & Mayer F. (2006). Muscle imbalances – fact or fiction? Isokinetics and Exercise Science, 14(1), 3–11.

Yeung, S. S., Suen, A. M., & Yeung, E. W. (2009). A prospective cohort study of hamstring injuries in competitive sprinters: preseason muscle imbalance as a possible risk factor. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(8), 589-594.

Dauty, M., Potiron-Josse, M., & Rochcongar, P. (2003). Identification of previous hamstring muscle injury by isokinetic concentric and eccentric torque measurement in elite soccer players. Isokinetics and exercise science, 11(3), 139-144.

Schneider, W., Biste, G., Freitag, P., Baumgartner, H., Tritschler, T., & Spring, H. (1989). Beweglichkeit: Theorie und Praxis. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme.

Gösele-Koppenburg, A., & Segesser, B. (2000). Anteriorer Knieschmerz – Fehlbelastungsfolgen im Sport. In: Das patellofemorale Schmerzsyndrom (pp. 96-105). Darmstadt: Steinkopff.

Knapik, J., Jones, B. H., Bauman, C. L., & Harris, J. M. (1992). Strength, Flexibility, and Athletic Injuries. Sports Medicine, 14(5), 277-288.

Brockett, C. L., Morgan, D. L., & Proske, U. (2004). Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(3), 379-387.